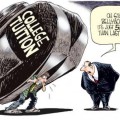

Part of the recent White House summit on making higher education more fundable was driven by the theory of “undermatching” – the idea that high-achieving low-income students should strive to gain entry into elite academic institutions rather than local community or public schools.

Part of the recent White House summit on making higher education more fundable was driven by the theory of “undermatching” – the idea that high-achieving low-income students should strive to gain entry into elite academic institutions rather than local community or public schools.

That was the message in a recent column by Patricia McGuire, president of Trinity Washington University. The Catholic university has 2,500 students, 80% of whom qualify for Pell grants.

McGuire’s column, first published on the Huffington Post and reprinted on The Washington Post, addresses one of the hot debates in higher education.

For business students the debate is a source of two areas of interest: the education angle, but also the business angle.

McGuire first notes what has been pointed by many different media outlets – most of the school officials invited to this month’s White House Summit on College Opportunity represented elite institutions. Only 2% of the universities represented at the summit have a student body where 70% of the students are using Pell grants, which McGuire wrote is “the best measure of low income students.” Additionally, she noted that 89% of the schools at the summit have a student body where half the students are using Pell grants.

Education, at least in theory, remains an area that is supposed to be a true meritocracy. The ideal is that good students should have a chance at higher education without their economic status being a consideration.

The question that undermatching raises, however, is what university they should attend to get that education.

From a business standpoint, McGuire is concerned that programs asking high school counselors to focus more on encouraging the best students to go to elite institutions will come at the expense of “less prestigious colleges that do a very good job serving low income students.”

McGuire also noted that such a focus also fails to consider that a low-income student may prefer attending a local college or university for a variety of reasons that have nothing to do with education itself, such as wanting to be near family or work.

There are also issues about the research itself. McGuire noted that students are placed into the “high-achieving” category based partly on SAT scores. Many students do not do well on standardized tests, she argued, and also that students who are good in one area might not be so good in other areas.

“The good writers sometimes don’t get it about algebra, and the math wizards can be clueless about commas,” she wrote.

She also questioned whether graduation rates and financial resources are proper indicators to assess the quality of a college. Graduation rates really only measure admissions risk and “brand loyalty,” McGuire wrote, noting that elite universities have huge pools of applicants from which they can choose the few who have the best chance at being successful students. Smaller schools cannot be as selective. She also argued in her column that all schools who serve poorer students need better “resources” (in other words, money) and not just the elite schools.