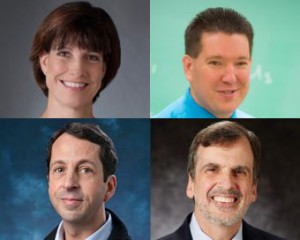

The four people honored as the 2013 U.S. Professors of the Year recently shared a common experience: how they learned from failure.

The four people honored as the 2013 U.S. Professors of the Year recently shared a common experience: how they learned from failure.

Their tales, told to the Chronicle of Higher Education, provide good lessons for students just preparing to start out in their careers.

The four winners were Ann Williams at the Metropolitan State University in Denver, Robert A. Chaney at Sinclair Community College in Dayton, Ohio, Gintaras K. Duda at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb., and Steven J. Pollock at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Williams teaches French and Chaney teaches mathematics. Both Duda and Pollock are physics professors.

The Professor of the Year awards are offered every year by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The four winners are picked from more than 350 nominees.

“The awards focus attention on excellence in undergraduate teaching and provide models to which others can aspire,” says a statement on the U.S. Professors of the Year website. Each award winner also receives a $5,000 from the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, an all-expense paid trip to the awards ceremony in Washington D.C. and an invitation to speak at the awards luncheon, among other honors, according to the website.

The professors shared some of the lessons they have learned from past failures with the Chronicle.

Williams said a challenge she always faces is getting a class to come together, because speaking a new language is an important aspect of learning it and students will only speak up if they are comfortable with each other. She said her failure has been not setting up the class properly to achieve that comfort level. However, she said past failures and experience has taught her various methods to achieve that comfort level, such as pairing timid students with confident students.

Chaney, the math professor, said he spent too much of his early career trying to be clever rather than focusing on student learning. He left academics for a time, pursuing a PhD and working in a nursing home. While there, he said, he learned humility, which allowed him to return to the classroom as a better teacher.

Duda, who teaches physics, said he started teaching in 2003 using a lab-based approach for his pre-med students. But after hearing repeated complaints from students that they wanted a more traditional, lecture-based class, Duda changed. He said that change is his biggest regret, and that he should have kept using advanced methods even though his students complained, because he knows those methods work. He is using project-based teaching for his upper level classes, but would like to return to those methods in his pre-med and introductory courses.

Pollock, who also teaches physics, said he regrets not asking more of himself and his students during his early days of teaching, when he was giving lectures to just three upper-level physics students. He said he did what everyone expected, but he wishes he had pushed for more, and in particular turned the class over more to the students. He now utilizes those approaches, even though he is teaching 60 students at the time.